The months leading up to the summer of 1862 had been tumultuous ones in the Kanawha Valley. After the Civil War broke out in the spring of 1861, Confederate forces attempted to recruit and organize regiments in the area but were soon pushed out by Federal forces moving in from Ohio. The aftermath of early battles such as Scary Creek and Carnifex Ferry left the valley secure for the Union and allowed the state-making process to continue in Wheeling. Federal troops entered Charleston on July 25, 1861.

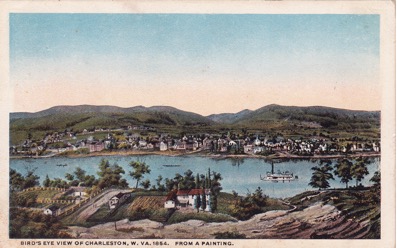

Charleston was not yet the capital city as we know it today. There were only 1,500 citizens living in Charleston in 1862, while the 1860 census listed 16,150 people living in Kanawha County, of which 2,164 were slaves. While Richmond had been the capital of Virginia, once the state seceded from the Union, Wheeling became the base for the new Restored Government of Virginia, loyal to the United States, under Governor Francis Pierpont. West Virginia would not become a state until June 20, 1863.

By the summer of 1862, a federal force of about 10,000 soldiers occupied the area under the command of future Ohio governor, General Jacob D. Cox, but events transpiring in Virginia led to the invasion of Maryland by Confederate forces under General Robert E. Lee. In support of meeting that threat against the nation’s capital, about 5,000 troops were transferred with General Cox to Maryland on August 11, 1862. Cox’s forces would participate in the bloody battle of Antietam, MD, on September 17, 1862, the Civil War’s bloodiest single day with more than 22,000 casualties.

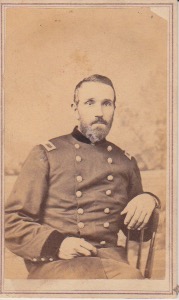

Left behind to defend the Kanawha Valley was a force of about 5,000 soldiers under the command of Lewis County resident, Colonel Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn. A childhood friend of famed Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, many will recognize his last name, having dined at his namesake restaurant, Lightburn’s, at the Stonewall Resort in Lewis County. Lightburn was commander of the 4th West Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment and was promoted to commander of the District of the Kanawha upon General Cox’s departure from the valley.

Confederate Major General William Wing Loring recognized the situation and moved quickly with a plan to retake the Kanawha Valley, which was a source for precious salt needed for meat preservation. On August 22, he dispatched Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins on a daring cavalry raid north of the Kanawha Valley. The Jenkins raid demonstrated that the Union defenses were inadequate and threw a scare into the local citizens.

Then, on September 6, Loring launched his command of around 6,000 Confederate troops out of the Narrows, near Pearisburg, VA, to move into the valley. His army turned back Union troops stationed at Fayetteville on September 10. The next day he engaged withdrawing forces at Cotton Hill and Montgomery’s Ferry near Kanawha Falls—not to be confused with the town of Montgomery. On September 12, Loring’s forces advanced on both sides of the Kanawha River towards Charleston.

Early Saturday morning, September 13, 1862, Charleston residents awoke to the sound of Confederate artillery shelling Union forces east of town. The Rebel guns were later moved to Fort Hill where they began a heavier bombardment. Federal troops countered with a weak barrage from a six-pound gun stationed near a barn on the Ruffner estate along Kanawha River in Charleston’s present East End. Union gunners also deployed a force to Watt’s Hill, on Charleston’s West Side, and commenced firing from there. Meanwhile, a spirited ground engagement took place near the site of the present State Capitol, one mile east of the present downtown, but then outside the city.

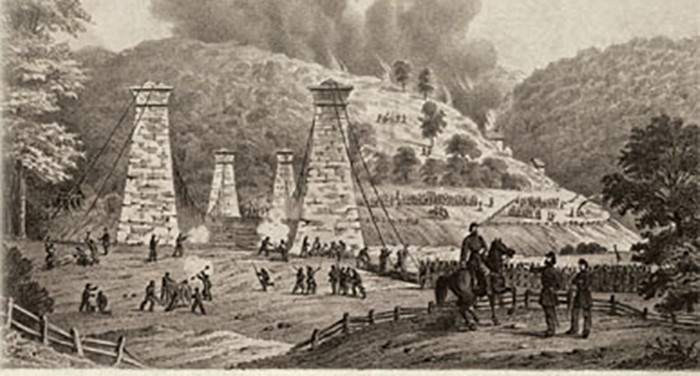

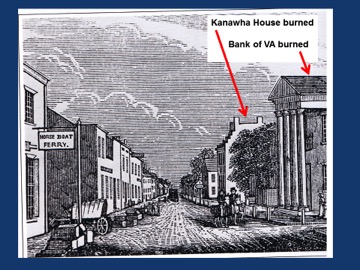

Around 11:30 a.m., Union troops withdrew to the area of present downtown Charleston. Colonel Lightburn notified civilians to evacuate the town and warned the Ruffner family to leave their homes along present Kanawha Boulevard. Confederates reached downtown around 3:00 p.m. and captured the Union garrison flag. In advance of his outnumbered army’s withdrawal, Lightburn ordered his Union troops to torch a number of downtown buildings rather than having them fall into enemy hands. They included Asbury Chapel, which had served as a quartermaster’s store, the Kanawha House Hotel, Bank of Virginia, Mercer Academy, two stores and several warehouses and cavalry barns. Retreating Federals then crossed the suspension bridge that carried present Washington Street across the Elk River and cut the bridge cables to slow pursuing Confederates. Dueling artillery batteries kept up a fierce bombardment west of the Elk until 5:00 p.m., and infantry skirmishes continued until dark, when the fighting ended.

Today, the Union Building stands on the site of the Horse Boat Ferry sign. Original image from Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Virginia, 1852.

Despite suffering a military defeat against superior odds, Union Colonel Joseph A. J. Lightburn is credited with maintaining a continual skirmish line along the 50-mile retreat to Point Pleasant, while keeping his 700-wagon supply train worth an estimated $1 million from falling into enemy hands. Unionist townsfolk and liberated local slaves joined in “Lightburn’s Retreat,” filling the Kanawha River with boats of all kinds and clogging the roads. The Confederate occupation lasted scarcely six weeks before Federals reoccupied the valley for the duration of the war. Confederate casualties in the 10-day Kanawha Valley Campaign numbered 18 killed and 89 wounded, while Union forces reported 25 killed, 95 wounded and 190 missing.

Author and historian Terry Lowry recently completed 10 years of research on this campaign, culminating in his book, The Battle of Charleston and the 1862 Kanawha Valley Campaign, published by 35th Star Publishing of Charleston. The comprehensive work contains 487 pages; 332 photos and images, many never before published; and 11 maps. Visitors to Charleston can also read about the battle on a series of historical markers along the Kanawha Boulevard.

For more information on Civil War history in West Virginia, visit www.wvcivilwar.com.